![]()

A Twice-Told Tale

I set out in search of the legendary food of France

and found the Holy Grail

This is a story with two happy endings.

There are certain writers who are able to project a culinary experience so vividly as to make their readers smack their lips in recollection of foods they may never have eaten. MFK Fisher’s “agonizingly curled” truite au bleu, brought to her in an empty dining room by a mad waitress and consumed amongst the aspidistras, or Elizabeth David’s pain d’ecrevisses sauce cardinal, eaten twice within a week in the austerely elegant dining room of Madame Barattero’s Hotel du Midi in the inaccessible upper reaches of the Ardeche—these take their place beside Proust’s little madeleine as vicarious, never-to-be-forgotten feasts of the imagination.

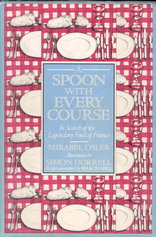

Mirabel Osler is such a writer. Is it because she made the literary leap into French cuisine after a long and distinguished career as a sensitive explorer of gardens, including the kitchen gardens that supply so many of its essential ingredients? Whatever the reason, her enchanting journal, A Spoon with Every Course: in Search of the Legendary Food of France, has become a vademecum of my gastronomic travels. Even the most modest among her twenty-one chosen restaurants are definitely, like Michelin’s treble-macaroned paragons, “worth a detour”.

Mirabel Osler is such a writer. Is it because she made the literary leap into French cuisine after a long and distinguished career as a sensitive explorer of gardens, including the kitchen gardens that supply so many of its essential ingredients? Whatever the reason, her enchanting journal, A Spoon with Every Course: in Search of the Legendary Food of France, has become a vademecum of my gastronomic travels. Even the most modest among her twenty-one chosen restaurants are definitely, like Michelin’s treble-macaroned paragons, “worth a detour”.

As with today’s artists, entrepreneurs and politicians, most of the chefs we see performing on TV or written up in periodicals receive attention because they have ambitiously engaged the services of agents who send out press releases containing all the essential ingredients of a journalistic confection. As Linda Grant has ruefully told us in the Guardian,

. . . comment is cheap and facts are just too expensive. Across what used to be known as Fleet Street foreign bureaux are being closed down. Newspapers are denuded of staff. Reporting skills are in decline.

If this is true of the people who shape or misshape our lives, how much more does it apply to those who merely give us pleasure! The days when Elizabeth David might be sent to scour the French countryside for archetypal bistros are no longer with us. Rarely can a food journalist afford to set out with laptop in search of first-hand information, and even more rarely will a publisher put the money up front for such a venture, unless it be to finance yet another pseudo-encyclopaedia of every dreary hole-in-the-wall available for eating or sleeping.

Mirabel Osler’s chosen eating places range from the grand to the homely, but the key word in her title is “legendary”. Legends are both ancient and simple: they exemplify and perpetuate the long threads of human culture at their most direct and economical. I suspect that her bias, if she has one, favors those unassuming cooks whose lives have been shaped, not by a thirst for fame or wealth, but by a quiet compulsion to do basic things with basic ingredients as well as is humanly possible. In the long run such a course, adhered to faithfully in a small community, is liable to attract the sort of regular diners that these modest artisans are happy to number among their friends.

And so I felt that Mirabel’s heart went out most warmly to Francine Foure, who single-handedly maintains a tiny ferme auberge at the end of a mountain road in the upper recesses of the Ardèche, a remote part of the Massif Central which is not exactly overrun with strangers. No passing trade here. Austerely located at the timber line, well away from the Gorge, with not a single tourist-seducing signpost, it must have felt rather like the remotest regions of the Ozarks (minus the murderous moonshiners).

You can’t just look up Montselgues in Michelin and book a hotel. The nearest place you can do that is Joyeuse, a mediaeval walled town only seventeen miles away but a good hour’s drive along precipitous hairpin roads. No, Chez Francine was not the place to go for a late dinner and then drive home after dark in an alcoholic stupor. Lunch was definitely the indicated option.

Last year Mary and I made the attempt on the way home from Provence, booking a B&B twenty miles away in Rocles, where Sawday’s trusty French B&B promised “good food, good conversation. . .and a vociferous quacamayo parrot.” Alas, it was not to be. Dubious crustaceans the night before had reduced both of us to quivering incapacity; and the next day, when we were somewhat recovered, Francine had to be away from home, which meant that her single-handed little auberge must close. When would such an opportunity come again?

In fact, it came just a year later (for me though not for Mary) when I was on my way to another ecological conference in Provence. With an Electric Phoenix concert in Hanover on a Sunday, I had four-and-a-half days to meander down to Les Marronniers, the Institute of Ecotechnics’ chateau just north of Aix. In the past, such a lax schedule has entangled me in a week’s laborious calculations, culminating in an agony of indecision. But this was my first major trip with the benefit of Microsoft’s AutoRoute Express Europe. This is a sophisticated CD-ROM route planning program which allows you to set up various destinations, indicate your average driving speeds on different types of roads, and choose alternative routes such as “quickest”, “shortest”, or “preferred”, in which you indicate a graded preference for various non-motorway or scenic options. This meant that I could plan a realistic schedule and make all my room and even restaurant reservations in advance, confident that I would not be forced into any last-minute Grand Prix against a stopwatch.

Taking travel a step further into the surreal, AutoRoute Express interfaces with GPS, the American military-developed Global Positioning System which takes readings from twelve satellites and tells you your exact longitude, latitude, altitude, speed, and direction of travel. If you’re travelling with a laptop, it traces a black line on a map on the computer screen, thus warning you whenever you’re approaching an intersection at which you must alter direction in order to follow the high-lighted route you’ve chosen. (Both laptop and GPS can run off the lighter socket.) Perched on a tray on my dashboard which I had installed next to the instrument panel, it constantly tells me where I am, the map scrolling automatically in the direction of my travel. It’s much safer than the usual alternative—an atlas balanced on the steering wheel—and is the only way I cheerfully allow Bill Gates to tell me where to get off. If only the rest of my life could be planned so rationally!

And so on this occasion I was able to make my luncheon reservation a month in advance. (Madame Foure likes at least a couple of days’ notice to come down from the mountain and do the shopping.) Leaving nothing to chance, I asked Mary Roe, a fluent French-speaking friend, to make the call for me. She reported that Francine sounded spry and in good spirits— news that Mirabel was very happy to receive, inasmuch as they hadn’t spoken for several years.

news that Mirabel was very happy to receive, inasmuch as they hadn’t spoken for several years.

This time I reserved a room for two nights in a B&B in Saint-Remèze, about an hour’s drive from Montselgues but close to the A6 motorway by which I would have to hurry to Les Marronniers by noon on Friday, lest I miss a splendid lunch. In the morning I asked my hostess, Madame Mialon (right), to phone Francine and confirm that I would be arriving. Detailed instructions for reaching Montselgues followed—a considerate but unnecessary gesture, given my sci-fi navigation electronique. Heart-in-mouth (or, being a whiting, tail-in-mouth) I set out in search of The Legendary Food of Madame Foure.

But first, a small side trip to Joyeuse, where Mirabel had found a cornucopia of local cheeses. The guide books don’t mention this little jewel of an old fortified town—it is too far off the usual tourist routes. It was the wrong day for marketing, but the empty streets, glowing in the unseasonal October sunshine, presented me with an enchanted slumbering kingdom, awaiting only my princely touch to bring it back to thronging vigorous life. I met with partial success: a gnarled old lady came out to greet me through her weather-beaten door flanked by baskets of chestnuts—labelled, not with their usual name, marrons, but with another name I didn’t recognize. (Perhaps it was in the ancient langue d’Oc: all the signs on the narrow twisting cobbled streets proudly, anachronistically, gave their names in both French and Provençal.)

But first, a small side trip to Joyeuse, where Mirabel had found a cornucopia of local cheeses. The guide books don’t mention this little jewel of an old fortified town—it is too far off the usual tourist routes. It was the wrong day for marketing, but the empty streets, glowing in the unseasonal October sunshine, presented me with an enchanted slumbering kingdom, awaiting only my princely touch to bring it back to thronging vigorous life. I met with partial success: a gnarled old lady came out to greet me through her weather-beaten door flanked by baskets of chestnuts—labelled, not with their usual name, marrons, but with another name I didn’t recognize. (Perhaps it was in the ancient langue d’Oc: all the signs on the narrow twisting cobbled streets proudly, anachronistically, gave their names in both French and Provençal.)

The chestnuts were hard and fresh, the tiny hairs at the blossom tip still downy as a baby’s cheeks. My ancient beldame, her limbs and body wrapped in brightly variegated strips of cloth like motley bandages, retreated indoors and returned bearing an ancient balance scale, which she held aloft with one hand whilst attempting to fill the pan and adjust the sliding weight with the other. It was almost more than she could manage; I had to fight an impulse to offer what would have been an insulting gesture of assistance. Once the kilo of beautiful chestnuts was safely confined in a plastic bag almost as ancient as her garments, she accepted my ten francs—a bargain price for such perfect produce, even though they lay everywhere along the roads waiting to be picked up—and went back indoors, perhaps to slumber for another hundred years.

Back on the road, I climbed further into the mountains, the black route line on my computer screen twisting like a drunken snake. The magic name MONTSELGUES appeared at last on a road sign, then the stone belfry of the village church with its austere Romanesque arches and the open square at the side where I had been instructed to park. Mirabel had arrived years before in a late spring flurry of “cookoo snow”; today there was a flood of equally unseasonal October sunshine, hot enough to melt my perfect-bound Michelin Road Atlas into an inconvenient loose-leaf edition.

Francine came out to meet me, noisily announcing her arrival with a clatter of wooden clogs. She was a tiny ageless bundle of energy, her brow free of wrinkles but her mouth and eyes lightly marked with the fine lines that come from a lifetime of habitual smiling. She kept up what was to me an incomprehensible chatter, though its tone spoke a warm welcome. Then. . . but let me turn back the clock and allow Mirabel to speak for us:

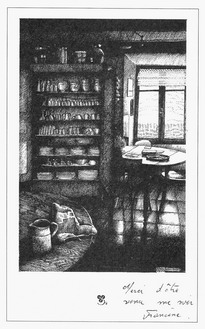

We pushed open the door and entered a low beamed room about twelve by sixteen feet. Apart from a serving table in the window five solid wooden tables filled the space, empty but for two men talking together in one corner. . . . From the rough-cast walls hung a cow bell, a calendar, a string of garlic, a storm lantern and various oil lamps. . . . Against one wall a cupboard stood open. Inside were shelves of glasses, bowls and crockery, the white sort that can still be found in markets. . . The shelves were bordered with crocheted cotton lace edging and a lace curtain covered half the glass of a door into the passage.

And there it all was, exactly as Mirabel had found it, even to the men at their table. (Were they the same men? Had they been waiting for me in suspended animation those intervening years?)

There was a pitcher of wine and a basket of dense rough bread on the table in the window, as in Simon Dorrell’s calm meticulous line  drawing for Mirabel’s book. As the eponymous courses arrived, it was as though they had slipped from between its pages. First, a big tureen of thick well-herbed bean soup with slices of rich fatty pork, its rind gently stewed into submission. Then a plate of hors d’oeuvres: sliced vine-ripened tomatoes stuffed with a moist mixture of fresh cheese and soft-boiled egg; Francine’s legendary terrine (“pork, lard, an egg, herbs of Provence, juniper and cognac”); thin-sliced chunky salami with large white lumps of fat; and wrinkled little marinated black olives that oozed well-seasoned oil when I bit into them. The rough local vin ordinaire (and your narrator) were soon tamed by the strong rich food.

drawing for Mirabel’s book. As the eponymous courses arrived, it was as though they had slipped from between its pages. First, a big tureen of thick well-herbed bean soup with slices of rich fatty pork, its rind gently stewed into submission. Then a plate of hors d’oeuvres: sliced vine-ripened tomatoes stuffed with a moist mixture of fresh cheese and soft-boiled egg; Francine’s legendary terrine (“pork, lard, an egg, herbs of Provence, juniper and cognac”); thin-sliced chunky salami with large white lumps of fat; and wrinkled little marinated black olives that oozed well-seasoned oil when I bit into them. The rough local vin ordinaire (and your narrator) were soon tamed by the strong rich food.

Right on cue, a hot tart:

. . . we had not anticipated eating anything as fragile. . . The crumbly pastry shells were filled with bacon and mushrooms covered in an eggy sauce. The savoury taste and creamy texture in contrast with the delicate pastry was something belonging to dining-rooms full of white napery and discreet lighting.

Next, with hardly a rest, a large grilled lamb chop, smothered (but not dominated) by a sharp cheese and mustard sauce. With it, Gratin dauphinois...

Next, with hardly a rest, a large grilled lamb chop, smothered (but not dominated) by a sharp cheese and mustard sauce. With it, Gratin dauphinois...

...with a crispy lid seasoned with thyme came straight from the oven to the table.

Then a local goat cheese, strong, ripe and hard, served from under the same well-worn wickerwork dome that Mirabel had noted years before. And finally, a rich tart with pureed apple and whole myrtle berries:

The pastry, made from chestnut flour, was thin; a mixture of eggs and sugar had been poured over the sliced apples and the whole concoction had been baked to the colour of Demerara sugar.

One of the men at the next table—the three of us were still the only diners—was modestly bilingual and I asked him what he did, knowing before he spoke that his answer would be straight from Mirabel’s pages:

—A bit of this, a bit of that.

When the time came for me to leave, Francine and I, who had hardly exchanged a comprehensible word, suddenly embraced, and tears came to both our eyes. It was like saying goodbye to an old and dear friend. Only in dreams have I experienced such profound déjà vu.

I wonder what author will next set down this tale, recreating our collective reality from his memory and his imagination.

§

A few hours later I was back at my B&B, retailing a part of my adventures over dinner. Our hostess, Sylvette Mialon, was obviously accustomed to serving good meals to appreciative guests and her husband Gérard was as devoted to the cellar as was his wife to the table. The others included two couples from Wüpperthal and a woman and her two children from Geneva, all of them friends and regular visitors. As I extolled the simple virtues of Francine’s cooking, I gradually became aware of what I was carelessly putting away. We had started with a loose vegetable paté made from aubergine, olive oil, garlic and basil; then tasty naturally reared pink veal, braised with home-grown onions, together with an egg custard and courgette gratin with a crispy cheese crust, and a dish of local carrots, lightly buttered and sweet beyond imagining. And to finish, an open pâte sucrée tart filled with figs and raspberries.

A few hours later I was back at my B&B, retailing a part of my adventures over dinner. Our hostess, Sylvette Mialon, was obviously accustomed to serving good meals to appreciative guests and her husband Gérard was as devoted to the cellar as was his wife to the table. The others included two couples from Wüpperthal and a woman and her two children from Geneva, all of them friends and regular visitors. As I extolled the simple virtues of Francine’s cooking, I gradually became aware of what I was carelessly putting away. We had started with a loose vegetable paté made from aubergine, olive oil, garlic and basil; then tasty naturally reared pink veal, braised with home-grown onions, together with an egg custard and courgette gratin with a crispy cheese crust, and a dish of local carrots, lightly buttered and sweet beyond imagining. And to finish, an open pâte sucrée tart filled with figs and raspberries.

It was food of a different generation, cooked by a woman who was Francine’s junior by thirty years or more, but partaking of the same devotion to unadorned simplicity—beginning with perfect ingredients, adding just what was necessary to bring out their essential character, and then stopping. It was the work of a chef whose principal condiment was not her ego, and it was accompanied by worthy wines, including a heady five-year-old Chateauneuf du Pape.

But we had only just begun. Gérard now took us down to his cellar for a postprandial tasting. In the middle of a stone-walled room lined with distilling aparatus and hundreds of bottles were three great oak barrels. He would prove to be a serious vintner, blender and distiller, both of wines and of various exotic liqueurs.

Next door, in a comfortable tasting parlour full of overstuffed furniture (to match the guests) we sampled a succession of his merlots and cabernets, and then worked our way through some of his more unusual liqueurs and eaux de vie. Such free-form spirits are a temptation to vulgar excess, but these were well-judged and preserved the identity of their basic ingredients. If they held a distinguishing charactaristic in common, it was their creator’s ebulient sense of humor! The culmination was a 1982 Cointreau—made, he asserted, by his mother-in-law—which, in its bouquet, delicacy and finish, well surpassed the familiar commercial product.

And so, as I declared at the offset, this is a story with two happy endings. I set out in search of the legendary food of France and found, not only the Holy Grail, but also a modern chalice of contemporary design, lacking, perhaps, the patina of age, but forged from the same unalloyed 24-carat gold. Despite the economic obstacles, the palate-deadening products of agri-business, and the siren songs of transitory wealth and fame—the ancient craft continues.

Chez Francine [Foure], Monselgues, Les Vans, 07140. TEL: 04 75 36 94 44

Sylvette et Gérard Mialon, La Martinade, 07700 Saint-Remèze, Ardeche,

TEL: 04 75 98 89 42, FAX: 04 75 04 36 30, e-mail: <sylvetlm@aol.com>

©1998 John Whiting

Return to TOP