“ … a better standard of ordinariness”

Le Duc de Richelieu

The new Paris bistros that get the most attention tend to be comets l aunched by Michelin stars as they threaten to disintegrate, deprived of the vital heat of endless world travel and unlimited expense accounts. These offshoots could be compared, perhaps unjustly, to the local shops opened or bought up by supermarkets in order to monopolize the casual trade as well as the expensive weekly shopping.

aunched by Michelin stars as they threaten to disintegrate, deprived of the vital heat of endless world travel and unlimited expense accounts. These offshoots could be compared, perhaps unjustly, to the local shops opened or bought up by supermarkets in order to monopolize the casual trade as well as the expensive weekly shopping.

And so it was intriguing to read of a new bistro near the Gare de Lyon which was described as “a throwback to the 50s and before”. No celebrity chef was touted, no steel-and-marble décor lauded, no month-in-advance booking advised. Nevertheless Le Duc de Richelieu got a week’s top billing in both Figaroscope and Pariscope. John Talbott reported this in his eGullet Paris restaurant digest, suggesting that “once the New York Times writes it up pre-summer, it will be too late.” That clinched it. And so we dropped by for lunch, wondering whether we would find an authentic period piece or a pop art extravaganza.

We needn’t have worried. At opening time there were lots of free places and there was nothing extraordinary in the décor except that it looked a bit new and shiny. A small piece of formica broken off the edge of a panel revealed that it was chipboard rather than the solid wood which would have prevailed in such an establishment half a century ago.

On the wall near our table was a clue as to why Le Duc had been set up with such a retro image. It was a newspaper clipping, yellowed with age, which announced the closure of a bistro with the same name at 110, rue de Richelieu. It had been the hangout of the Paris-Press journalists – “consorting with Miss Gigondas” was the secretarial euphemism when they were out slopping up the wine – but it closed down when Paris’s equivalent of Fleet Street dispersed to the outer city.

On the wall near our table was a clue as to why Le Duc had been set up with such a retro image. It was a newspaper clipping, yellowed with age, which announced the closure of a bistro with the same name at 110, rue de Richelieu. It had been the hangout of the Paris-Press journalists – “consorting with Miss Gigondas” was the secretarial euphemism when they were out slopping up the wine – but it closed down when Paris’s equivalent of Fleet Street dispersed to the outer city.

The most complete historical record of the original Au Duc de Richelieu, at least in English, is to be found in Gaston Wijnen’s Discovering Paris Bistros, a guide first published in 1991. He writes that it served

…good home cooking, which daily attracts journalists from the local newspaper offices, clerks and directors from the neighbouring banks, and local inhabitants; in short, a heterogeneous crowd … All the wine … comes directly from the growers where Monsieur Georgé, the patron, has been sampling, selecting and buying for more than thirty years … Monsieur Georgé … is carefully aging them as well.

A short blackboard list of proprietary wines [right] suggests that the link between the old and new bistros might indeed be this wine merchant or his successor. I shall make an effort to find out.

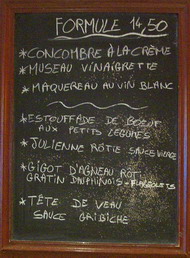

There was a blackboard with a dozen entrées and thirteen plats, but we chose to order  from the 14.50€ menu on a separate board. We started with Cocombre à la crème and Maquereau au vin blanc, both of which were unremarkable but acceptable. My main course however, Estouffade de boeuf aux petits legumes, was utterly sensational, a melt-in-the-mouth beef stew which must have been braised in the requisite red wine for the full eight hours. I accompanied it with a half bottle of the house Morgan, excellent value at 13€.

from the 14.50€ menu on a separate board. We started with Cocombre à la crème and Maquereau au vin blanc, both of which were unremarkable but acceptable. My main course however, Estouffade de boeuf aux petits legumes, was utterly sensational, a melt-in-the-mouth beef stew which must have been braised in the requisite red wine for the full eight hours. I accompanied it with a half bottle of the house Morgan, excellent value at 13€.

Two days later at Les Ormes I would have their highly regarded jarret de veau braisé à la cuiller, a similarly rich, densely flavored stew which was equally as good as the estouffade but no better – either could easily have been eaten à la cuiller, “with a spoon”. (Les Ormes’ dish was of course almost twice the price – we were helping to pay for a posh location near Invalides and lots of starched linen.)

Mary’s main course from the set menu was, remarkably for such a traditional bistro, vegetarian: Julienne rôtie sauce vierge, a bed of thin-cut roasted vegetables, with other conventionally boiled vegetables on the side, which she found delicious. I had a taste, but my attention was centered on my incredible estouffade. Wanting to be certain that we could face a full dinner that evening, we decided to forego dessert. The bill for this modest but excellent feast: an equally modest 44€.

As we left, Mary suggested that we return for lunch the following day, a thought that had already crossed my mind and with which I readily concurred.  Arriving shortly after opening, we were greeted by the same waiter as though we were regulars. He showed us to the same table and when I suggested that our names should be inscribed there on a plaque, he agreed with a chuckle.

Arriving shortly after opening, we were greeted by the same waiter as though we were regulars. He showed us to the same table and when I suggested that our names should be inscribed there on a plaque, he agreed with a chuckle.

This being a Saturday, there was no set menu, so we happily consulted the carte. My immediate first choice was the intriguing Andouille d’escargot, which proved to be a dozen snails, not in their shells but roasted on a bed of chopped sausage in a rich tomato sauce – not something I had encountered before, and quite delicious. Mary’s Asperges vinaigrette was cold and of the continental white variety, which those who are used to hot English green asparagus often find disappointing.

For a main course we both chose that old cliché, Confit de canard avec pommes à l’ail. Warhorse it may have been, but it was an inspired performance. The confit was crispy-skinned, the meat within of a tenderness and succulence that could have been consumed by a toothless grandsire. A half-bottle of moulin a vent at 13€ lubricated it nicely.

And the garlic potatoes! – perfectly cut to the “thickness of a half-crown”, as a chef from London’s Connaught Hotel instructed Mary they should be. They were golden brown, crisp around the edges but soft within the thin outer shell. Like the heavenly pommes salardaise we once ate in the Dordogne, we would happily have sat down to a meal consisting of nothing more.

As we were congratulating ourselves for having preceded the barbarian hordes, a voice across the room enquired of the waiter, “Do you speak English?” “Do you speak English indeed!” I exclaimed to Mary. “It’s the beginning of the end!” A Frenchman at an adjoining table laughed aloud. Fortunately the newcomer turned out to be only a Middle-European searching for a common language.

This time we had no compunctions about staying on for dessert. Mary’s Tarte aux fraises was a perfectly good example and my own generous helping of cantal cheese, ripe and rindy, was a bargain at 5.4€. It required another glass of moulin a vent to do it justice.

Waverly Root tells of a French critic whose test of a new restaurant was to order a salade de tomates, just to see how much effort they would put into its preparation. Mary’s equivalent is to ask at the end of the meal for a hot chocolate. The more elevated establishments don’t often have it, but much may be learned from the manner in which they respond. On this occasion, not only were they able to oblige, but the generous cupful was excellent – rich and chocolatey.

My own espresso was no doubt flawless, but I was in such a state of euphoria that I would probably have tossed back a Nescafe in perfect contentment. To round out the feeling of well-being, I accompanied it with an Armagnac. Our collective enjoyment must have registered with our waiter, for he poured me another Armagnac which I felt obliged to consume in order not to appear ungrateful. The bill for all this self-indulgence came to a hundred euros.

Perhaps I should not be sharing the secret of this time warp with my readers, but I think it will probably survive unscathed. The Gare de Lyon is not an area teeming with tourists – those who make the effort will likely be those who deserve it. There is nothing remarkable about Le Duc de Richelieu. In fact, it is perfectly ordinary. But in the astute words of English food historian Jane Grigson, “We have more than enough masterpieces; what we need is a better standard of ordinariness.”

Le Duc de Richelieu 3 rue Parott, 12th, Tel: 01 43 43 05 64, Mº Gare de Lyon ____________________________________________________________________

July 2005: A walk along the Promenade Plantée led inevitably to luncheon chez le Duc. We were recognized immediately by the maitre d’ (my conspicuously enthusiastic greed during our previous visits may have had something to do with it) and we were brought an aperitif to nudge us along the way to further excess.

With a major dinner in the offing, for a starter I limited myself to half-a-dozen snails, while Mary worked her way leaf-by-leaf through a huge artichoke, served with a milky/creamy vinaigrette. (Heavy irony: The new improved manche-tout variety doesn’t seem to have reached this primitive outpost of civilization.)

Mary went on to a suprème de pintade à la crème (a creamy mushroom sauce, with a mountain of rice), while I took advantage of the rare appearance of cervelle de veau aux capres—an entire calf’s brain with the traditional sauce gribiche. There’s a distinct advantage in being too old to come down with various long-term food-induced fatal illnesses.

To finish (just because it was available) I disposed of a large slab of very mature cantal with a thick moldy rind. I’m sure that an English health inspector would have pronounced it well past it’s sell-by date—but then, so am I, so we were perfectly matched.

A pichet of the house Morgon washed it all down.

Back to the beginning of this review

Return to INDEX