L'Ecurie

From Through Darkest Gaul with Trencher and Tastevin, 1997:

Sophie returned, then F., & we walked up Mouffetard to L’Ecurie in rue du Mont S. Geneviève for dinner [160]: we had

Salade de tomate

Paté

saucisson

selle, côte d’agneau & chateaubriand

crèpes aux poires flambé

vin en pichet

If I read this correctly, that was a three-course dinner for four, including wine, for 160 francs—cheap even twenty years ago. Last year Charles returned and found the restaurant unchanged except for the prices, and those had not kept pace with inflation. These are the very restaurants that are fast disappearing, and so a visit was mandatory.

I went on a sunny evening (one of the few this sodden summer) and found an ancient seedy building whose decor, inside and out, could best be described as Dickensian Hippie. The facade was the sort of black which might have begun decades ago as any other color, with decoration which included a couple of brightly-painted cartoons and an amazing tattered photo of an ancient bearded gentleman on an enormous tricycle, a parodic Horseman of the Apocalypse. Over the sidewalk hung a sign with a stylized representation of a strutting Etruscan stud. The tables inside were crowded and higgledy-piggledy, so I opted for a small table on the sidewalk in the sun with the grill just the other side of an open window. There I could enjoy everyone else’s dinner as well as my own.

I was immediately brought a glass of sangria, a basket of bread, and a generous dish of aïoli which must have kept the staff occupied all day crushing the garlic. The aroma wafting through the window told me that my first course had to be grilled marinated sweet peppers and tomatoes, brushed with the marinade and sprinkled with basil. These proved to be succulent even beyond expectation. For a main course I settled on grilled lamb chops and French fries and was rewarded with lamb which tasted simply of lamb and fries which tasted of potato. My only mistake was to pass up the house wine for an indifferent Provencal rosé. Subsequently I would adopt the maxim,

Don’t stray

From the cliché,

Just stay

With the pichet!

At the end of a leisurely meal I was brought a glass of calvados. (Like the sangria, it came with the territory.) By then the restaurant had filled up and a young couple with a baby, evidently friends of the staff, were regretfully informed that there was no room in the inn. Observing a star in the East, I stood up and offered them my table, which they gratefully accepted. Conversation revealed that he was himself a restaurateur, in charge of a riverside restaurant at the Bastille which was mentioned in one of my guide books. It was his night off. I was reassured; “Eat where the chefs eat,” is my motto.

He proved to be very familiar with L’Ecurie and knew something of its history. The building itself, he thought, went back to the 16th century and the ground floor had been a restaurant for at least a hundred years. I would later discover that the bar inside was an original zinc. This was the metal from which they were usually made, so that it became the generic term even when the bar was wood or even plastic. Alas, this became common during the last war, when almost all of the zinc bars were melted down by the Germans. This is one of the few to survive, and the maker’s seal is evidence that it dates from just after the Great War (as opposed to the others).

My informant went on to tell me that L’Ecurie was noteworthy for the excellence of its meat and also its super gambas. I would be able to verify this at lunch the following day. Not wanting to suffer the near-fate of my new acquaintances, I made a reservation for one o’clock. But first I would have to move from my luxury hotel in the 1st Arrondisement, paid for by IRCAM, the computer music research center established by Pierre Boulez—the great good place where worthy electroacoustic composers go when they die. Since I was remaining in Paris between weekends at my own expense, I opted for a B&B on the south edge of the Latin Quarter.

Back at my sidewalk table, soon to bear my name on a brass plaque, I ordered the super gambas. Four of them arrived on a large platter. They were are biggest king prawns I’d ever encountered; I would have hesitated to engage them, live, in single combat. Chewy and succulent, they were a meal in themselves, but were nevertheless accompanied by an enormous baked potato, which I had discovered was an optional substitute for the fries. Having chosen the low-fat alternative, I proceeded to drown it in aïoli. I’m a true American: I always drink calorie-free Badoit with my Ben & Jerry’s super-rich vanilla ice cream.

As I ate my lunch an over-decorated woman of a certain age was pulled past me, as if on wheels, by three identical toy dogs on identical leashes. She had also passed by the evening before. I was beginning to feel at home.

ON A ROLL (to coin a phrase), I booked dinner for seven-thirty that evening. I was to meet James Wood, a fine English composer with whom I’ve worked for twenty years. James is someone I have always bitterly resented. Possessing a voracious appetite for fiery vindaloos, he has been known to tuck into my left-overs; and yet he could model for an Oxfam poster. The explanation must be metabolic. (I refuse to accept the alternative that he simply works harder than I do.)

ON A ROLL (to coin a phrase), I booked dinner for seven-thirty that evening. I was to meet James Wood, a fine English composer with whom I’ve worked for twenty years. James is someone I have always bitterly resented. Possessing a voracious appetite for fiery vindaloos, he has been known to tuck into my left-overs; and yet he could model for an Oxfam poster. The explanation must be metabolic. (I refuse to accept the alternative that he simply works harder than I do.)

James had the incredible fortune of working in Paris for a month on a new piece at IRCAM. With his world reputation as a lover of good food, introducing him to L’Ecurie could guarantee its survival well into the next millennium.

I began by following James’ example, a blue cheese salad. It was a simple large bowl of lettuce with a creamy blue cheese dressing, and then a surprise at the bottom, some more crumbled bits of blue cheese. This is contrary to the usual restaurant practice, which is to fill the bowl with lettuce and then put the expensive bits on top where they’re visible. A whole day’s crab salads may thus be gleaned from a single crustacean.

My main course was again lamb, but this time a grilled slice of leg cut straight through the bone. Both these courses plus a desert (my choice being a cassis sorbet packed with bits of ripe fruit), were among the alternatives in the bargain menu at 98 francs.

When was the next time I could make an excuse to return? What about the following evening, when I was to meet T. Wignesan, the Stateless Civil Servant? (That’s the title under which I’ve told him he must publish his autobiography.) Wignesan (who refuses to divulge what the T stands for—is it perhaps his Tantric identity?) is a research fellow in comparative literature and was a long-time friend of the late poet and scholar Eric Mottram. Friends of Eric belong inexorably to a world-wide club from which, like the Catholic church, there is no resigning. I knew Wignesan to be a vegetarian, but I had no compunctions about bringing him here and steering him towards the aïoli and the grilled peppers, while I had a salade de tomates. This is a simple dish which Waverley Root used to choose as a means of testing a restaurant. If the waiter raised his eyes in haughty disdain and brought an unadorned dish of sliced tomatoes, the establishment failed. L’Ecurie passed easily with a generous plate of ripe fruity slices discreetly dressed and herbed.

Being a tolerant man and possessed of a long-suffering wisdom, my companion watched without impatience as I gobbled down a grilled skewer of lamb, peppers and onions. Our reminiscences of Eric took us late into the night. By the time we left I was almost rooted to my now-familiar spot. Perhaps I shall leave provision in my will that I am to be embalmed and, like the corpse of Jeremy Bentham, seated in a glass cage from which I may preside over this venerable institution for all eternity.

IT WAS several days before I would return. By then Mary had joined me in Paris and, not surprisingly, chosen L’Ecurie as the venue for our one dinner in Paris on our own. I suggested that she join me in an entrecôte, which she usually rejects in restaurants because she dislikes rare meat. Confident that the chef would oblige, I told her to order it well done. She was rewarded with a bloodless steak which was still juicy, tasty and tender—the first, she affirmed, that she had really enjoyed other than at home.

Towards the end of our meal James appeared after a long day’s work at IRCAM and occupied an adjacent table. He has since told me that he returned so often that he was virtually adopted into the family. Thus, centaur-like, he is now an ecurie in his own right. I hope it doesn’t exhaust his creative powers.

FIVE YEARS LATER: In between our explorations of unfamiliar bistros we returned for lunch a couple of times to our old friend L'Ecurie, to which I devoted three pages in Through Darkest Gaul. Off and on, this site has housed a restaurant for perhaps a couple of centuries and, in its present form, has been known to Charles Shere at least since 1977, when he entered details of a meal in his day book, and to me for the past five years. During this latter half-decade not a single item on the set menu has altered, nor have the unlisted accompaniments.

On being seated you are presented with a glass of iced sangria; then comes a basket of good pain levain and a generous ramekin of as garlicky an aïoli as you could wish for. My chosen first course is always a dressed green salad liberally sprinkled with bleu de auverne, often followed by a generous lamb chop from the saddle - good French lamb, and woe betide the diner who suggests otherwise. This comes with a generous helping of frites or, alternatively in the evening, a baked potato. To wash it down, a demi-pichet of perfectly drinkable red wine. My desert is invariably sorbet cassis de maison, with small bits of black currant. Finally, along with the coffee, a complimentary glass of a good calvados.

At lunch all this will set you back around 120ff, at dinnertime around 150. If you want to lash out on the à la carte, 110ff will get you a plate of what another Paris restaurateur swears are the best giant prawns in town. I have no evidence to the contrary.

If the weather permits we usually dine at a table in front on the sidewalk Just inside the door a curve of ancient narrow stairs winds down into a stone-walled basement and, below that, a roman-arched vault with a long refectory table that could easily seat twenty or more. What intimations of immortality surround you here!

If

I lived in Paris I would form a society whose sole purpose would be to dine

weekly in this redolent echoing chamber.

If

I lived in Paris I would form a society whose sole purpose would be to dine

weekly in this redolent echoing chamber.

L'Ecurie and its disappearing siblings are for me the ultimate foundation upon which public communal dining is based. If it were the restaurant at the end of the world, I would count myself lucky and order my last meal in perfect contentment.

L'Ecurie, 2 rue Laplace, 5th arr. Tel:01.46.33.68.49

©2001 John Whiting

2007: Mary, Frank and I returned for lunch and found this old institution still lodged in its time warp. The super gambas are as superlative as ever and hardly raised in price. They are so rich that by the time I had finished using the finger bowl, it would have made a very decent soup. The accompanying bread and the aioli are unchanged. Frank paid only 12.50€ prix fixe for his three-course lunch; that's 0% inflation! Mary and Frank ended their meals with a well-constructed fresh fruit salad.

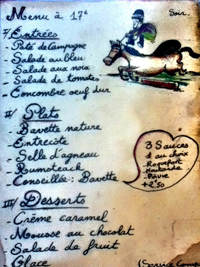

2012 A friend has just been there and found it just as I remembered. The basic menu is now €17 -- still very reasonable. You can read Natacha's report here: http://devonium.wordpress.com/2012/07/24/a-classic-paris-bistro/.

2013 We were back at our beloved L’Ecurie again for the first time since 2007. Madame still presides and the prix fix menu remains a giveaway 17€. The welco

2013 We were back at our beloved L’Ecurie again for the first time since 2007. Madame still presides and the prix fix menu remains a giveaway 17€. The welco ming glass of sangia still magically appears, then the bread and bowl of aîoli, and at the end the warming shot of calvados.

ming glass of sangia still magically appears, then the bread and bowl of aîoli, and at the end the warming shot of calvados.

Some details, alas, are not the same. The super gambas are no longer the enormous succulent objects they once were. (I'm sure those monsters have become prohibitively expensive.) And the aîoli seems to have been tamed for feeble palates, so that Mary’s tuna and aîoli were not as she remembered. However, my paté de canard was both excellent and plentiful. All things considered, it is amazing that this establishment has been able to hold its ground against the inexorable advance of gastronomic anonymity.

Madame has an innate generosity that is rare in the restaurant business or in any other. When I presented her with a copy of Through Darkest Gaul, in which L’Ecurie featured as long ago as 1997, she tried to pay me for it. Long life to you, dear Madame, and to your unique and irreplaceable hostelry!

Back to the beginning of this review