![]()

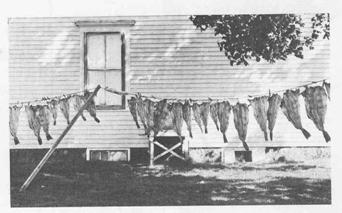

salt cod was the backbone of Provincetown’s prosperity. After whaling moved to Nantucket and New Bedford, the town continued to produce the basic food supply for the sugar plantation slaves of the West Indies. Even after slavery was abolished by the British, French and Dutch a couple of decades before the US got around to it, odoriferous displays of drying fish – as in this old scene just a few blocks along Commercial Street from the house where I grew up – still dominated the landscape.

salt cod was the backbone of Provincetown’s prosperity. After whaling moved to Nantucket and New Bedford, the town continued to produce the basic food supply for the sugar plantation slaves of the West Indies. Even after slavery was abolished by the British, French and Dutch a couple of decades before the US got around to it, odoriferous displays of drying fish – as in this old scene just a few blocks along Commercial Street from the house where I grew up – still dominated the landscape. The salt cod that went to feed the slaves had to be cheap, and so the processing was quick and careless. Henry David Thoreau visited a Provincetown fishery two centuries ago and wrote laconically of its quality control:

The cod in this fish-house, just out of the pickle, lay packed several feet deep, and three or four men stood on them in cowhide boots, pitching them onto the barrows with an instrument which has a single iron point. One young man, who chewed tobacco, spat on the fish repeatedly. Well, sir, I thought, when that older man sees you he will speak to you. But presently I saw the older man do the same thing.

Bacalhau (salt cod) is such an integral ingredient in Portugese cuisine that there is reputed to be a different recipe for every day of the year. However, among the Portugese who fished from Provincetown, these dishes were largely absent. Perhaps it was because they knew too much about the unlisted ingredients! In 1983 Mary Alice Luiz Cook, a local fisherman’s daughter, wrote down a collection of Provincetown Portugese Recipes which she realized were in danger of disappearing. There is not a single salt cod recipe among them.

Provincetown’s most famous chef, Howard Mitcham, is explicit about this in his Provincetown Seafood Cookbook:

Although Provincetown made tons of it for export they ate very little of it themselves, and never developed an extensive salt codfish cuisine; they made an occasional salt codfish hash for breakfast and that was just about it. With all the fresh fish and shellfish around, Provincetown did not have to lean too heavily on the preserved varieties.

He goes on to apologize that the bacalhau recipes for his book had to be borrowed from Spain, Portugal, Provence and Italy.

THERE was one variation which continued to be made in Provincetown up to my own youth. This was Skully Joe, a lethal weapon you could “bend lead pipe around”. By this time commercial salt cod had diminished in pungency, prominence and profitability; but “fisherman’s candy” was still hung out to dry in a few back yards. Captain Kemp, the old clipper ship skipper next door, kept the ceiling of his shed hung with it like stalactites in some prehistoric cave. Sometimes he would give me a rock-hard hunk to suck on and its briney quintessence of fishiness would keep me occupied for an hour or more.

THERE was one variation which continued to be made in Provincetown up to my own youth. This was Skully Joe, a lethal weapon you could “bend lead pipe around”. By this time commercial salt cod had diminished in pungency, prominence and profitability; but “fisherman’s candy” was still hung out to dry in a few back yards. Captain Kemp, the old clipper ship skipper next door, kept the ceiling of his shed hung with it like stalactites in some prehistoric cave. Sometimes he would give me a rock-hard hunk to suck on and its briney quintessence of fishiness would keep me occupied for an hour or more.

When I first encountered salt cod in the south of France, my experience with Skully Joe led me seriously astray. I brought a bag of it home and put it away in the garage. It was midsummer and an odd smell gradually suffused the car’s upholstery. By the time I had located the source it had practically been reduced to Roman garum. Skully Joe would still have been suckable come judgement day.

FOR those with hardy determination and laid-back neighbors, Mitchum gives detailed instructions on how to make this formidable snack. If you undertake it you may be able to corner the market; even the Ptown Portugees don’t make much any more.

___________________________________________________________________________________

You should use cod, haddock, or pollock of 1 or 2 pounds in size. Since it's hard work you should make a batch of a hundred or more. (Don't go mooching them from the poor fishermen; shell out some cash and buy a boxful when the price is right.) You don't have to scale them or cut off the fins. just cut off the head and gut them by splitting down the body to about an inch below the vent hole. After scraping out the innards you hold them under a running faucet, and, using a toothbrush, brush off the stomach lining and blood, and most important of all, the blood clots near the backbone.

Next you make a brine of the quantity needed to cover your fish. The old Cape Cod way of making brine is to lay a medium‑sized potato on the bottom of the container, fill it with water and then add salt and stir slowly until the potato rises to the surface and floats. (A quicker way to approximate this is to use 1 quart water to 1 pound of salt.) To make Skully Joes easy to handle you tie them together at the tails by twos with strong cord; they are slick when they come out of the brine, and the cord with a fish on each side also provides a handy way of hanging them up. You soak them in the brine for 12 to 20 hours, then you hang them out in the back yard on the clothesline for 3 days of sunshine. Moisture must be avoided at all costs; take your fish in at sundown to avoid dew and frost and if it's rainy or foggy do not put them out at all.

If there are any bluebottle flies around, they usually won’t attack a well‑salted fish, but just to be doubly safe you should pack about 1/4 teaspoon of salt at the upper end of the split by the tall, which is where any residues of blood or oil are most likely to seep out. At the end of the third day of sunning you can move them to a shed, or an attic or a cellar; drive nails in a rafter or joist, and drape a pair of fish over each nail. (Do not put them in a furnace room or they will dry out too fast.) At the end of 10 days they should be ready to eat.

And there's also the fine old Yankee version of sugar cured Skully Joe. To achieve this effect you add a pint of Porty Reek Long Lick or long tail sugar to each 2½ gallons of brine. Porty Reek Long Lick and long tail sugar, of course, is old Cape Cod lingo for molasses. Or you can just use a pound of sugar. Now this kind of Skully Joe really will draw flies, so you must build a screen box to dry them in. Didn't I warn you this business could become complex?

I didn't warn you that Skully Joes throw off a very strong smell. After the cure is finished, they should be stored in airtight plastic garbage bags and hidden in some far off corner of the house, say the garage, or the tool shed. To eat 'em you take a sharp pocket knife and cut off a chunk and chew on it. Or if you want to be dainty about it and you happen to have an electric table saw, you can saw them up fast into bite-size squares. Dear Emily Post and Amy Vanderbilt, I know your ghosts is shudderin' at this salty old Cape Cod custom of Skully Joe, but that's how it is, take it or leave it.

Howard Mitcham, Provincetown Seafood Cookbook, 1975, Addison Wesley, pp186-7

_________________________________________________________________________

Footnote: Mary Alice Cook’s Traditional Portugese Recipes from Provincetown is introduced by Grace Goveia Collinson, who was the first Provincetown Portugese fisherman’s child to graduate from college. Shortly thereafter she was my fifth grade English teacher and helped me form my life-long excitement in the presence of good writing. It wasn’t until half a century later, when we spent half the night getting reacquainted, that I learned how her unique scholarship to Mt. Holyoke had carried with it the condition that she renounce her church. What cultural arrogance those puritanical do-gooders were capable of!

___________________________________________________________________

SALT COD PUREE

Brandade de Morue

Serves 8

GOOD SALT COD is filleted but not skinned before salting. If buying a section of fillet, avoid the tip of the tail and the abdominal flaps. The best part lies directly behind the abdomen. It may require from 24 to 36 hours soaking in repeated changes of cold water, preferably placed skin side up in a colander immersed in a large basin. Check with your merchant for soaking times. When it is ready, it will have doubled in volume and noticeably whitened.

Brandade is often served as a first course, scattered with tiny croutons fried in olive oil. Except for the Christmas Eve gros souper, Lulu nearly always serves it spread on individual croutons to accompany the aperitif. She emphasizes the importance of including the skin, whose gelatinous content binds the puree while lending it, at the same time, a soft, voluptuous texture.

Court-Bouillon

1 bay leaf

4 garlic cloves, crushed

3 cups water

1 pound salt cod, soaked (see above)

4 tablespoons olive oil

3 tablespoons milk

Thin slices of baguette, partially dried in a slow oven or in the sun and rubbed lightly with garlic [or fried in olive oil if calories don’t matter JW]

Combine the fennel, bay leaf, garlic, and water in a saucepan, bring to a boil, and simmer, covered, for 30 minutes. Strain the courtbouillon and leave it to cool. Place the salt cod, skin side down, in a saucepan just large enough to contain it, pour over the cold courtbouillon, and if necessary to completely immerse the cod, some cold water. Bring slowly to a boil, cover the pan tightly, turn off the heat, and leave to poach in the cooling liquid for 15 minutes. Remove the fish, drain it, and pick it over, removing any bones, flaking the flesh and tearing the skin to pieces.

In a food processor, process the flesh and skin for a few seconds. In a small pan, heat about 1 tablespoon of olive oil until very hot. At the same time, put the milk to warm. Add the hot olive oil to the fish, process, warm the remaining oil to hot but not smoking, and whir in about 2 tablespoons. Add about 2 tablespoons hot milk and, if necessary, a little more olive oil and milk until the puree is creamy and consistent, neither too firm nor too loose. Spread it on the garlic croutons and serve warm.

[N.B. THIS IS STRONG! You might want to moderate with potato puree and/or more garlic.]

From Richard Olney, Lulu’s Provençal Cookbook: The Exuberant Food and Wine from the Domaine Tempier Vineyard, New York, HarperCollins 1994, pp83-5

_______________________________________________________________

Fausse Brandade

GROWING up in Provincetown, I early acquired a taste for salt cod in the form of a local specialty known as Skully Joe, or fisherman’s candy. Cap’n Kemp, the retired clipper ship skipper who lived next door, used to dry his own in the shed which bordered our back yard, and he’d give me a morsel which I’d suck on carefully, making it last for an hour or more. I didn’t encounter the French classic, brandade de morue, however, until years later in its natural habitat.

GROWING up in Provincetown, I early acquired a taste for salt cod in the form of a local specialty known as Skully Joe, or fisherman’s candy. Cap’n Kemp, the retired clipper ship skipper who lived next door, used to dry his own in the shed which bordered our back yard, and he’d give me a morsel which I’d suck on carefully, making it last for an hour or more. I didn’t encounter the French classic, brandade de morue, however, until years later in its natural habitat.

Last January I returned from Harstad, north of the Arctic Circle in Norway, with some of the best salt cod I’ve ever laid my hands on. I promptly made it into brandade, following Lulu Peyraud’s recipe as set down by Richard Olney in Lulu’s Provençal Kitchen. From the beginning the texture and aroma were promising and it proved to be worth all the soaking, steeping and blending: the finished product was strong with that traditional salt cod flavor, robust but not aggressively coarse.

It’s a crime to get through all that wonderful stuff in a couple of days, so I followed my usual practice of partially freezing it in a large rectangular tray, then cutting it into segments which go into a plastic bag and are returned to the freezer, to be thawed one by one as needed. It’s strong stuff, and it’s precious, so I usually follow the effete Parisian practice of mixing it with mashed potato.

Yesterday I had a craving for another fix, so I went to the freezer and took a small square from my dwindling supply. How long would it last? As I prepared to eat it, a little can sitting on the counter gave me an inspiration. I scrubbed and cut up another 1/4 lb of potatoes and put them to simmer with some fennel seeds and a bay leaf. When the potatoes were soft enough to mash I put them in the food processor with a dash of milk, added a couple of pressed cloves of garlic, some pepper and sea salt, and—wait for it—the entire contents of a 4-oz can of sardines packed in olive oil.

I threw the switch and gave the mixture about 15 seconds to blend thoroughly. Nearby was a warm dish of the Real Thing. Trembling with anticipation (and when I tremble, the earth moves), I tasted one and then the other. Miracle of miracles! Aside from their color they were astonishingly similar. And the fausse brandade had taken no more than five minutes to make (plus potato boiling time) as opposed to the hours of looking for decent salt cod, the overnight soaking, the simmering of the court-bouillon, the gentle steeping, the careful removal of the bones, and the lengthy pounding in of the warm oil and milk. True, the sardine mixture had an aftertaste of sardines, but no matter; I’m quite fond of sardines.

It was a major breakthrough for culinary science. I felt like stout Cortez, silent upon a peak in Darien. I needn’t treck back to Harstad after all, or even ask Santa to pick up some on his way from the North Pole; this was actually better than some real brandade I’d made with strong, stringy salt cod bought in Britain. Mary’s already decided to include it in her next cookbook. I won’t give up making the real thing, but for ersatz brandade, this is good enough to tell the world about. Which is exactly what I’m doing.

©1998 John Whiting

As printed in John Thorne's Simple Cooking

Return to TOP

Return to RECIPES INDEX